This is the advice each and every fiction writer has heard perhaps hundreds of times. And it’s solid, right?

How lame is it to say “Joe Bob was sad” when you can instead tell us “Joe Bob stared at the frayed lace of his shoe, winced, squinted, allowed a tear or wept in the bald bright light of day, the uncut grass around him thrumming with heat and insects. That he sighed or brayed or let escape an embarrassing sob, pressed a Kleenex to his face. Etc. etc. etc.

But an interesting discussion on Agent Nathan Bransford’s excellent blog got me thinking about this particular writerly rule. I suspect that many well-respected authors break it willy-nilly when the story or style or needs of the plot call for maverick acts of authorial daring.

I pulled a couple of random books from my shelves to demonstrate.

These are excerpts from the beginning pages of Ian McEwan’s Atonement:

“She was one of those children possessed by a desire to have the world just so.”

And “Her wish for a harmonious, organized world denied her the reckless possibilities of wrongdoing. Mayhem and destruction were too chaotic for her tastes and she did not have it in her to be cruel.”

And this from the beginning chapter of Chuck Palahniuk’s Invisible Monsters:

“Where you’re supposed to be is some big West Hills wedding reception in a big manor house with flower arrangements and stuffed mushrooms all over the house. This is called scene setting: where everybody is, who’s alive, who’s dead.”

Some telling serves a purpose. In McEwan’s, perhaps, it’s to establish a certain authority and tone. With Palahniuk, the details (I know the details are actually “showing”) and telling are to establish a certain voice.

Does it matter? Or do we readers slip under the fictive dream (Think John Gardner coined this phrase) and let slip our concern with rules?

I’ve noticed that a lot of published writers have maverick tendencies. Rules broken left and right, POV switches and sentences sans subjects and so much telling, hell even exposition—10 pages about the history of whaling to use an extreme example-- when the text seems to call for it.

And we readers take it. Hell, we love it.

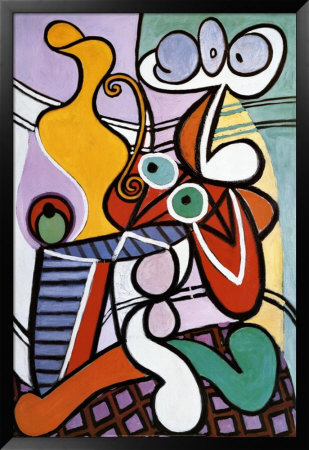

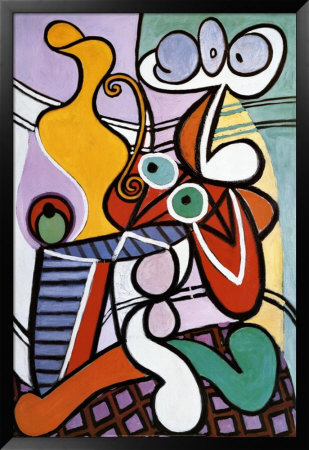

A long, long time ago, I spent a few misguided years in the world of fine art, sketching from

models, dreaming of a glorious future of linseed oil and loft space, and in that short period, I learned that one has to know the rules—how to draw a perfectly lifelike basket of fruit—

before one can go all Picasso on it.

The viewer can tell the difference.

I suspect that the reader can as well, and that we have an instinctive feel for competence, can tell when a writer could provide us a damn good portrait if she wanted to and once a clear competence is established, we are eager to see where a little experimentation will take us.

What do you think?

1 comment:

I've had this post up all day trying to think of how to respond, but my brain is such mush right now.

I do remember what my 8th grade art teacher used to preach which was 'learn to look and see.' It always used to aggravate me, because how can you not do both? But I think he pretty much meant what you wrote about here.

Post a Comment